Austin Frakt is a physician who writes about health economics with some health economists and other researchers. He has summarized several studies that show how

doctors change their behavior when they are paid for services versus paid via capitation.

Fee for service payment of physicians is often blamed as a

contributor to high and rapidly growing health care costs. In an

analysis of primary care physicians, Helmchen and Lo Sasso provide a sense of how physicians respond to different compensation schedules:

Using a four-year [2003-2006] sample of 59 physicians and

1.1 million encounters, we study how physicians at a network of primary

care clinics responded when their salaried compensation plan was

replaced with a lower salary plus substantial piece rates for encounters

and select procedures. Although patient characteristics remained

unchanged, physicians increased encounters by 11 to 61%, both by

increasing encounters per day and days worked at the network, and

increased procedures to the maximum reimbursable level.

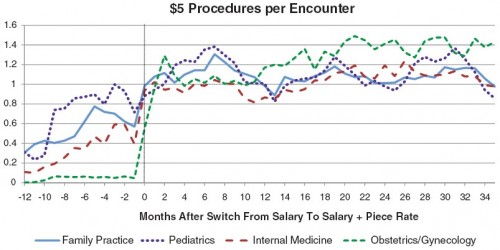

The extra payment that so dramatically increased encounters was $5

for each reported performance of an eligible procedure. The number of

procedures per encounter in each month that qualify for the $5 bonus is

illustrated in the following figure by practice area:

The policy implication is obvious, right? Paying fee for service is

asking for higher costs. So, we could cut costs by reducing or

eliminating piece rate based (fee for service) payment. Case closed.

Not so fast! Let’s talk about what those $5 bonus payment eligible procedures were.

[T]he network began paying physicians $5 for each

reported instance of most immunizations for children and adults as well

as counseling and screening services aimed at detecting or preventing

risk behaviors such as substance abuse, contraction of infectious

disease, suicide, obesity, and the patient’s exposure to violence.

Importantly, physicians were only remunerated for an average of one $5

procedure per encounter.

It is not at all obvious that the extra money spent encouraging these

particular procedures was not worth the personal and population health

value they conferred. Put it this way, would you argue that the

individuals who received those services should not have, that those

services were part of the problem of overuse of unnecessary care? That

is a hard argument to make. Yet the data show that without the extra $5

the studied physicians provided fewer of those very services.

As the authors point out, to make that precise, one would need to

quantify the health gains and adjust for whether the provision of extra

services by these physicians didn’t just offset a reduction of services

by others for the same patients (crowd out). By doing so, it is possible

to make a good argument that more health spending is worth the cost (see my post

on Cutler’s book that makes this very argument, but with numbers.) This

is important to keep in mind. Fee for service isn’t all bad. It just

needs to be applied in a more nuanced way. Not all physician compensation should be fee for service. But some should be.

And

another study found sick patients do poorly under a capitation scheme whereas healthy people do poorly under a fee-for-service payment scheme.

In case there is any doubt, a new study using experimental methods shows

that how physicians get paid and by how much does affect patient care,

but it is not the only factor. The health of patients matter too.... The paper, by Heike Hennig-Schmidt, Reinhard Selten, and Daniel

Wiesen, appeared in the Journal of Health Economics and is titled How payment systems affect physicians’ provision behaviour—An experimental investigation. As the title states, this was an experiment, not an observational study.... the findings:

- Payment systems matter. More services are provided under FFS than

CAP. On average, patients receive more services than are optimal under

the former and fewer than optimal under the latter.

- Patient health matters. That is, physicians do respond to how much

treatment benefits patients. Still, under FFS, patients in good and

intermediate health are overserved. Under CAP, patients in poor and

intermediate health are underserved.

- Payment systems affect health (or patient benefit). Patients in good

and intermediate health suffer losses under FFS due to overprovision.

Patients in intermediate and poor health suffer losses under CAP due to

underprovision.

It should be perfectly clear from these results why patients in the

real world might self-sort according to health, even aspects of health

that are unobservable to the researcher. A patient in poor health

attempting to optimize his benefit would do better under FFS. A patient

in good health gets better results under CAP.

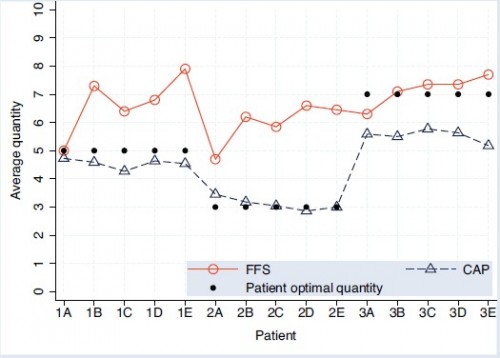

Even though I already stated the results, the following chart conveys them so beautifully you really must take a look....

A-E are the (abstract) illness types and 1-3 index how much medical

care would be optimal. The solid, black dots show the optimal level of

care. Patients of type 1 (1A, 1B, etc.) would do best with 5 units of

care, etc. Notice that under both payment systems, actual quantity

provided is correlated with what would be optimal, highest for type 3

patients, lowest for type 2. So, patient needs matter. Still, patients

needs don’t tell the whole story. Provision of care under both payment

types differs from optimality, most strongly for types 1 and 2 under FFS

and type 3 under CAP. Finally, CAP levels of care are systematically

lower than under FFS.

Conclusion: money matters, though so do patients. Lesson: your

doctors, or medical providers generally, are not just taking care of

you. They’re taking care of business (themselves) too.